Detroit's Segregation PastBlack Neighborhood |

|

|

Text by Photos by |

THE BEGINNING From its pioneer days, Detroit's population was a mixture of ethnic and racial backgrounds, including black residents. The city survived on fur trapping and trading before it moved on to processing iron ore, building stoves, railroad cars and finally automobiles. Other important industries were paint/varnish, pharmaceuticals and shipbuilding. The growth and prosperity of the city brought many job seekers to Detroit. In the Great Migration of African-American people of the World War I era, thousands of black people from the American South came north for jobs, many finding a home in Detroit and a job in the auto factories. Growth of the auto industry in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s brought more people into the city. During the war years of the 1940s when factories hummed round the clock building war goods, housing was particularly scarce. The city reached its population peak of almost two million people in the prosperous post-war 1950s. It was a busy big city of single-family homes with yards, good schools and pretty parks. 1920s to 1960s - PARADISE VALLEY 1960S - URBAN RENEWAL SEGREGATED LIVING - THE TRIAL OF DR. OSSIAN SWEET Dr. Sweet had grown up in Florida where he had seen Negroes killed by white mobs. He had been in the thick of a riot, a white mob invading black neighborhoods, when he was attending medical school in Washington DC. His wife Gladys had grown up in Detroit, actually living in a white neighborhood, and did not have the same level of fear of her new neighbors. Dr. Sweet, with his memories of racial violence, had recruited friends for protection and had stocked a closet with guns, just in case he had to actually defend those inside. The baby was staying with relatives. The crowd grew noisy and some threw rocks at the windows. Dr. Sweet thought he heard someone breaking in and, in fear, distributed the guns to the men inside the house. Amid the turmoil, a car pulled up with Dr. Sweet's brother and a friend who were immediately threatened by the crowd. Shots were fired from the Sweet house and several men who were in the street were hit; one of them was killed. The police, who had not done much to disperse the crowd or protect the people in the house, demanded entry and began arresting everyone.

Hostility toward blacks moving into a white neighborhood was fueled by real estate agents and mortgage companies whose practice was to downgrade the value of houses in a neighborhood with even one black resident. The white familes who struggled to pay mortgages felt they had to protect the value of their homes, and that meant keeping out Negroes. The Ku Klux Klan, with a large membership in Detroit, fueled the idea that blacks were an inferior race whose presence degraded the Anglo-Saxon ideal, providing an excuse for racial prejudice. Darrow successfully showed that Dr. Sweet and the others were faced with a mob who they believed, based on past incidents, meant to harm them, and they had a right to defend themselves. But, sadly, housing segregation continued in the city. Why had the previous owner sold the house to Dr. Sweet, knowing his neighbors would object? The answer according to Coleman Young, who, as a young boy, did errands for Dr. Sweet, as related in Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Coleman Young, is because the prevous owner was a light-skinned black man passing for white. Young's book provides a look at life in a highly segregated city and another excellent book gives you the whole fascinating tale of Dr. Ossian Sweet and the events leading up to the famous trial. This book is Arc of Justice by Kevin Boyle. I highly recommend these two books. Today, the Sweet home still stands and has a historical marker on its front lawn. 1942, VIOLENT REACTION AT SOJOURNER TRUTH PUBLIC HOUSING

The Sojourner Truth Public Housing project still exists on Nevada Street in Detroit. It continues to be occupied as public housing. THE HOT SUMMER OF 1943: 34 DEAD IN RIOTING Mayor Edward Jeffries appealed to Governor Harry Kelly for help. Martial law was declared and 2500 federal troops arrived on Monday night to try to end the riot. Unfortunately, on late Monday afternoon, police approached a hotel at John R and East Vernor where blacks (described in the 1969 book All Our Yesterdays as a "a group of fear-crazed Negroes") were barricaded. Those inside fired on police who promptly returned the fire, shooting many volleys into the hotel. The gunfight went on until a number of people inside were dead and some policemen were wounded. Violence continued in the days that followed. Troops remained until June 30, patrolling the city and enforcing a curfew until a measure of calm returned to the city. When it was over, 34 people had been killed and many more injured in the rioting. BREWSTER-DOUGLASS PROJECTS In later years, a number of well-known people (including Diana Ross and the Supremes) would grow up in the Brewster Projects. However, interest in public housing began to wane in the 1960s and Brewster, along with other public housing developments in the city, became less desireable. Rampant crime began to destroy the formerly family-friendly environment. Instead of waiting lists, public housing projects became mostly empty units in search of tenants. Brewster-Douglass was completely abandoned by 2008. Don't look for these buildings today; four remaining high rise buildings were demolished in 2014. An adjacent low-rise development, New Brewster Homes, continues to be offered as public housing and is mainly occupied by senior citizens. GOOD LIVING: CONANT GARDENS ALMOST SUBURBIA: 8 MILE & WYOMING Blacks also settled across Eight Mile Road (Detroit's northern boundary) into an area of Royal Oak Township which never was annexed by adjacent suburbs of Oak Park and Ferndale. This little enclave of black history still exists as Royal Oak Township. THE RETURN OF RIOTING: JULY 1967

Police, acting on previous orders of Mayor Cavanaugh and Police Commissioner Ray Girardin, refrained from taking tough action against the rioting crowd. Cavanaugh had integrated city agencies and instituted policies for police to exercise restraint when dealing with dissidents. He had joined 125,000 black and white marchers led by Dr Martin Luther King in 1963 as they marched down Woodward Avenue in support of civil rights for blacks. He did not expect to be presiding over a city in racial turmoil. Hadn't the city moved beyond the problems of 1943? I have a personal connection to the 1967 riot, which left 44 people dead. I experienced it first-hand, up close and personal. See my own story of living through a riot, Detroit: From Industrial Giant to Empty Landscape. My husband and I were newly-weds, living in an apartment just a mile or so from where the riot began. The previous stories on this page are history, their content from my collection of books on Detroit and its history and from museums and historical markers around the city. But, I don't need a book, a museum or a historical marker to tell me what happened in July, 1967. I was there, right where it started, and I KNOW the enormous impact it has had on the city of Detroit. The city's problem with mass abandonment of homes, neighborhoods and businesses can be traced in great part to the civil disturbance of July 1967. (July, 2013: Governor Rick Snyder, in his press conference concerning Detroit's filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, says there are 78,000 abandoned structures in Detroit waiting for demolition. Now THAT'S serious abandonment!!) The long history of racial separation and the animosity it breeds was lurking in the streets of the city in the summer of 1967, exploding into a violent week of rioting and looting. The riot accelerated the city's decline, with so many people leaving that the city's population shrunk by two-thirds, houses stood empty and crime took over. Studying what went before (the incidents related on this page) shows the origins of these problems go way back in the city's history. We need to come to a time when, to paraphrase President Barack Obama: There are no black neighborhoods. There are no white neighborhoods. There are just neighborhoods. 1974 — DETROIT GETS ITS FIRST BLACK MAYOR: COLEMAN A. YOUNG Young had grown up in Black Bottom, his parents having migrated from Alabama. As a young man growing up in an urban culture, he was intimately familiar with its usual vices like illegal gambling and the numbers racket, and he participated in such nefarious activities as shoplifting and smuggling booze from Canada during Prohibition. He liked to hang out at Maben's Barber Shop and discuss the political happenings in the city. During World War II, he trained as a Muskegee Airman, but never served. His activism got him in trouble and he was grounded. In public life, he never minced words or let up on those he saw as enemies. Mayor Young worked well with the white business leaders and was on good terms with President Jimmy Carter from whom he obtained federal funds for a variety of projects, but Mayor Young was mostly the mayor of black Detroit, not of what was left of white Detroit. He had an abrasive personality, and had little use for some of the white people who might have supported him out of liberal sentiment. In his autobiography, he refers to these types as "bleeding-heart, pansy-ass liberals." To get my thoughts on living under Mayor Young (I lived in the city while he was mayor), see my review of his autobiography, a book well worth reading. It is full of the colorful expletives for which hizzoner was known, but also provides insight into a unique time in Detroit's history, as it transitioned to being a predominantly black city. Like him or not, Coleman Young left his mark on the city he loved and led for 20 years. 2014 — DETROIT GETS A WHITE MAYOR Detroit is 85% black, yet they elected Duggan to be the first white person to serve as mayor since 1974. Why? Most who are asked this question say because he was the best candidate, more qualified and more likely to fix the city's problems than his opponent, Wayne County Sheriff Benny Napoleon. So, does his election mean we are living in a post-racial era? Probably not, judging by the many current scandals around our country involving white police harassing and killing black people. More likely, Detroiters are simply fed up with crime and are desperate enough to put aside the issue of race. It didn't hurt either that Duggan campaigned vigorously in the black community, attending some 200 backyard parties in every part of the city and even winning the endorsement of the black ministers. He was tireless and fearless in pursuing the office of mayor. It seems to me that most of us are willing to look past race when we see no threat, no harm to us or our way of life, in choosing a candidate with a different racial identity from us. Apparently, black people trust Mike Duggan, just as many white people trusted Barack Obama and voted for him. The fact that whites have adopted much of black culture and that middle-class blacks live and talk pretty much like middle-class whites has eliminated a large portion of our differences. This may not be apparent to young people, but, for me, growing up in the 1950s and coming of age in the 1960s, the difference between then and now is huge. |

SOME PLACES TO VISIT IN DETROIT

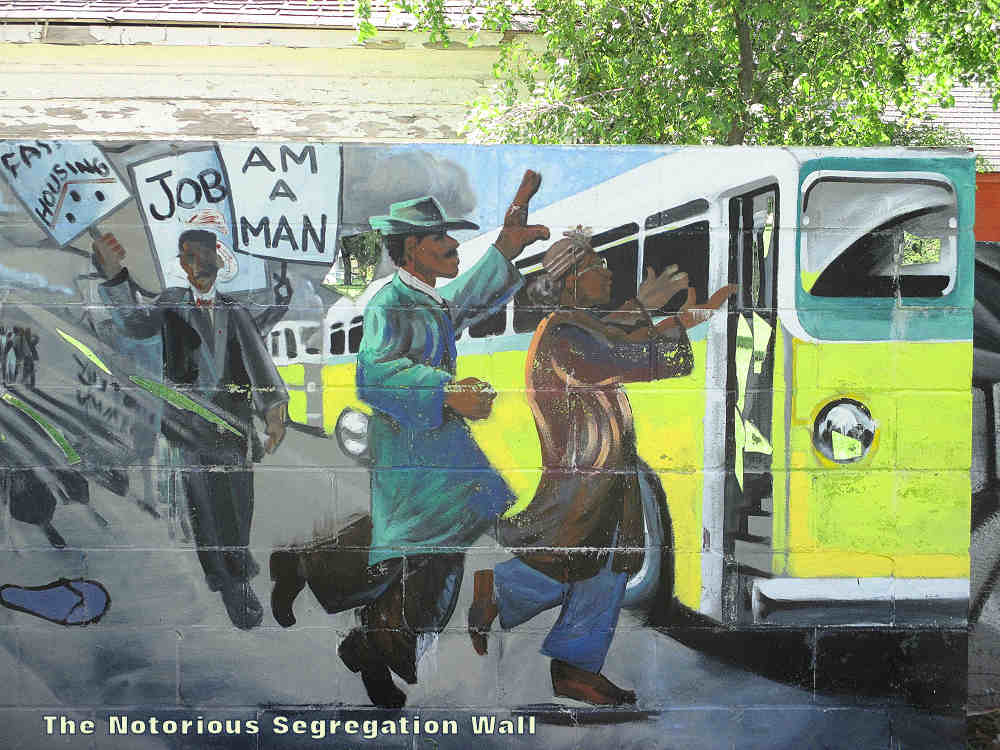

THE SEGREGATION WALL | |

|

DETROIT, 8 MILE-WYOMING Built in the 1940s by a developer so he could get federal financing for an all-white subdivision, "The Wall" separated black-occupied homes from an area designated for whites. Today this "wall of shame" stretches along Alfonso Wells Memorial Playground just south of Eight Mile Road and west of Wyoming, also running behind houses north of the park. The wall is covered with a colorful mural suggesting its history and purpose as a barriar between black and white neighborhoods, but reflecting a desire for peace and understanding. |

|

|

THE SEGREGATION BALLPARK

The Stars played in three different parks over their existence, first at Mack Park on the East Side until it burned down in 1929, then in Hamtramck Stadium (shown in these photos) and playing their final year at DeQuindre Park. The Detroit Starís greatest player was Turkey Stearnes, a prolific home run hitter who played center field. He also worked in the auto plants because he could not live on what he made playing baseball. Many immortals of baseball played here, including the great pitcher Satchel Paige. The remains of the ballpark still stand in a corner of Veterans Park in Hamtramck. The city of Hamtramck owns it and is seeking a historic designation for it with hopes of preserving it for the future. The stadium is just one of five remaining ballparks that were home to Negro League baseball teams. As black players were accepted in the major leagues and their minor league affililates, the Negro Leagues gradually vanished into history, another legacy of segregation. |

|

By Theresa Welsh It's July, 1967 and my wedding party was a riot. And How a Once-Bustling Neighborhood Turned into Empty Countryside thousands of abandoned homes throughout the city Abandoned Packard Plant Abandoned Fisher Body Plant Detroit Discards Become Unique Urban Art

BOOKS ABOUT DETROIT

|

Detroit's Spectacular Ruin:

The Packard Motor Car Company built luxury vehicles that set the standard for excellence in styling and engineering in the early 20th century. The huge complex of Albert Kahn-designed buildings was a fixture on East Grand Boulevard, employing as many as 40,000 workers. Its 3.5 million square feet inside the city of Detroit encompasses numerous structures. Packard cars were built here until 1956 when the site was repurposed, but it gradually became vacant, the beginning of a new life as an iconic and most-visited urban ruin. eBook for Kindle and Other eReaders Only $6.95 BUY FROM: |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

BOOKS ABOUT DETROIT Click on a book image below to go to amazon.com for more information. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Seeker Books Home Page More Detroit photos at